Lifestyle factors have been studied at length in relation to Parkinson's Disease and there is good evidence that having ever smoked is associated with reduced risk of the disease. Alcohol drinking has also been linked to reduced risk of disease, and multiple studies have looked at the association. The difficulty with drawing robust conclusions in this area relates to the design of the studies - many of the studies are case control, taking people with and without the disease and asking them to report whether and how much they drink now and in the past. This kind of study suffers from problems with bias - if you have been diagnosed with the disease you are more likely to have attended hospital, to be the kind of person who worries about their health and so makes more health-conscious choices, you may recall things differently in light of your diagnosis and you are likely to have made different choices subsequent to diagnosis.

Longitudinal studies of populations who are healthy at baseline are less likely to suffer from these biases as reporting of alcohol consumption is made prior to subsequent diagnosis. This problem with investigating causation in medicine is illustrated nicely by a study published in the Journal of Neurology by a Spanish team. They looked at 31 studies in the field and broke down the analysis into different types of study as well as looking seperately at men and women and different ways of classifying alcohol consumption.

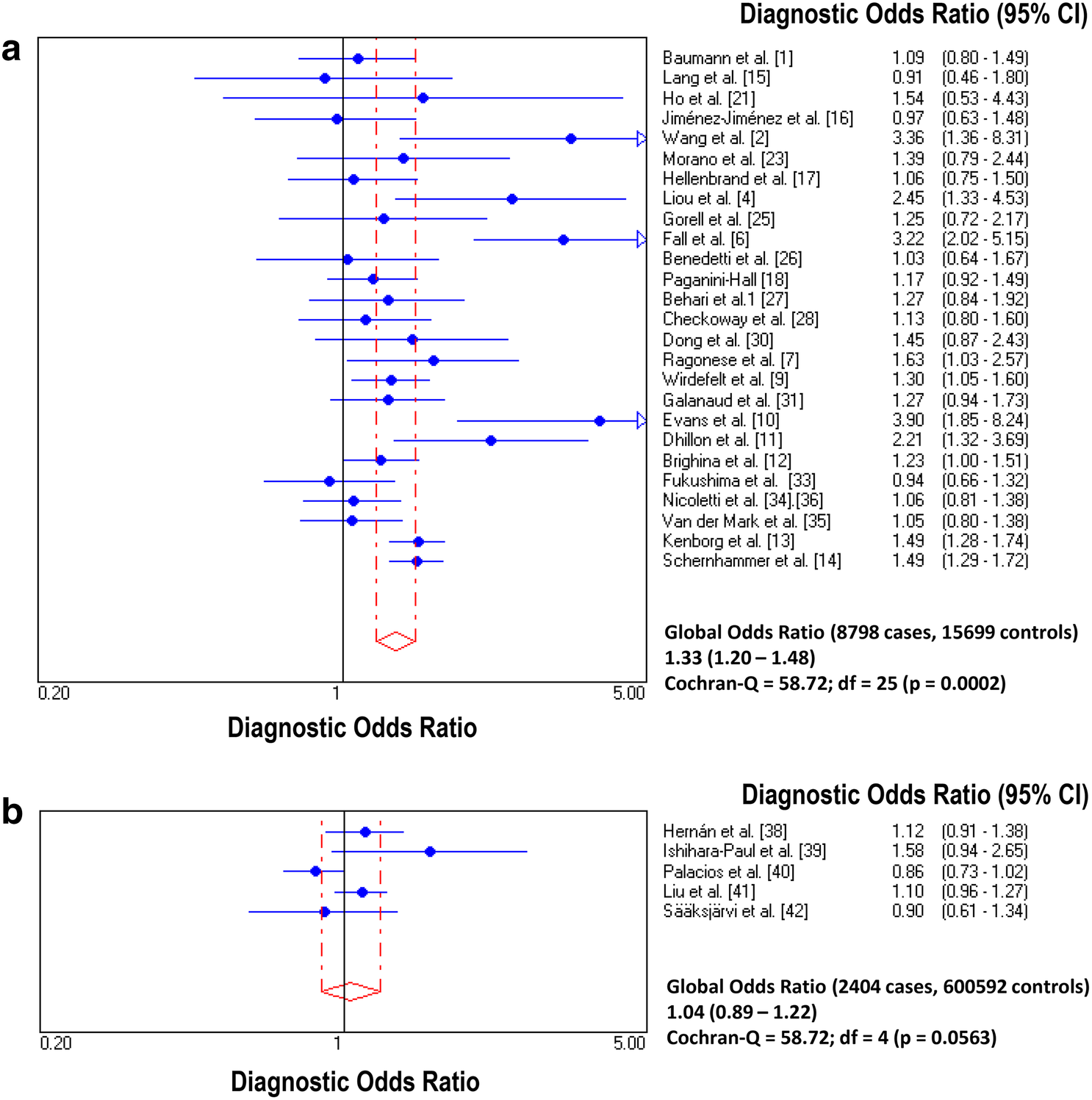

When looking at the case-control studies, as in previous studies, they found higher numbers of 'never-drinkers' in the group with Parkinson's. However, when looking at longitudinal studies, there was no difference in having ever drunk alcohol between people who went on to develop Parkinson's and people who didn't. However, there were far more case-control studies in the article, giving more power to detect these kind of effects, as you can see in the diagram below.

All in all, alcohol consumption remains an interesting part of the puzzle of Parkinson's causation, especially given possible genetic links the authors discuss between variants of the alcohol dehydrogenase gene which cause adverse effects of alcohol and dopaminergic function. In the PREDICT-PD study we are collecting data on alcohol use in all of our participants and will continue to study these links.

-Anna

Longitudinal studies of populations who are healthy at baseline are less likely to suffer from these biases as reporting of alcohol consumption is made prior to subsequent diagnosis. This problem with investigating causation in medicine is illustrated nicely by a study published in the Journal of Neurology by a Spanish team. They looked at 31 studies in the field and broke down the analysis into different types of study as well as looking seperately at men and women and different ways of classifying alcohol consumption.

When looking at the case-control studies, as in previous studies, they found higher numbers of 'never-drinkers' in the group with Parkinson's. However, when looking at longitudinal studies, there was no difference in having ever drunk alcohol between people who went on to develop Parkinson's and people who didn't. However, there were far more case-control studies in the article, giving more power to detect these kind of effects, as you can see in the diagram below.

|

| Pooled odds ratios comparing "never drinking" to "ever drinking"alcohol in a)case control and b)prospective longitudinal studies, showing higher likelihood of Parkinson's disease in those who never drank in case control but not longitudinal studies. From https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00415-018-9032-3 |

-Anna

J Neurol. 2018 Aug 28. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-9032-3. [Epub ahead of print]

Alcohol consumption and risk for Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Jiménez-Jiménez FJ, Alonso-Navarro H, García-Martín E, Agúndez JAG

The possibility that alcohol consumption should be considered as a "protective factor" for Parkinson's disease (PD) has been suggested by several case-control studies. However, other case-control studies and data from prospective longitudinal cohort studies have been inconclusive. We carried out a systematic review which included all the eligible studies published on PD risk related with alcohol consumption, and conducted a meta-analysis according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The systematic review was performed using two databases, and the meta-analysis of the eligible studies with the software Meta-Disc1.1.1. Heterogeneity between studies was tested with the Q-statistic. The meta-analysis included 26 eligible retrospective case-control studies (8798 PD patients, 15,699 controls) and 5 prospective longitudinal cohort studies (2404 PD patients, 600,592 controls) on alcohol consumption and PD. In retrospective case-control studies the frequency of PD patients never drinkers was higher and the frequency of heavy + moderate drinkers was lower [diagnostic OR (95% CI) 1.33(1.20-1.48) and 0.74(0.64-0.85)], respectively, when compared to healthy controls. In contrast, in prospective studies, the differences were not significant with the exception of a trend towards a higher frequency of non-drinkers in PD women and a significantly lower frequency of moderate + heavy drinkers in PD men in those studies which stratified data by gender. The present meta-analysis suggests an inverse association between alcohol consumption and PD, which is supported by the results of case-control studies but not clearly by prospective ones.